Images

Participants

Contact

Two articles produced by Joan Guinovart’s lab answer key questions regarding the activity of glycogen in neurons.

An excess of glycogen causes neuronal death while a lack of this polysaccharide endangers these cells under oxygen shortage to the brain.

In 2007, in an article published in Nature Neuroscience, scientists at the Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB Barcelona) headed by Joan Guinovart, an authority on glycogen metabolism, suggested that in Lafora Disease (LD), a rare and fatal neurodegenerative condition that affects adolescents, neurons die as a result of the accumulation of glycogen—chains of glucose. They went on to propose that this accumulation is the root cause of this disease.

The breakthrough of this paper was two-sided: first, the researchers established a possible cause of LD and therefore were able to point to a plausible therapeutic target, and second, they discovered that neurons have the capacity to store glycogen—an observation that had never been made—and that this accumulation was toxic.

Other reports defended a different theory and upheld that the glycogen deposits were not cause by the neurodegeneration but were a consequence of another, more important, cell imbalance, such as a down deregulation of autophagy—the cell recycling and cleaning programme. In several articles, Guinovart’s “Metabolic engineering and diabetes therapy” group has recently brought to light evidence of the toxicity of glycogen deposits for LD patients, and has now provided irrefutable data.

In an article published at the beginning of February in Human Molecular Genetics, with the research associate Jordi Duran as first author, the scientists show that in LD the accumulation of glycogen directly causes neuronal death and triggers cell imbalances such a decrease in autophagy and synaptic failure. All these alterations lead to the symptoms of LD, such as epilepsy.

Glycogen, a Trojan horse for neurons?

There was still a greater mystery to be solved. Was glycogen synthase truly a Trojan horse for neurons, as apparently established in the article in Nature Neuroscience? That is to say, was the accumulation of glycogen always fatal for cells, thus explaining why their glycogen synthesis machinery is silenced? The inevitable question was then why these cells had such machinery.

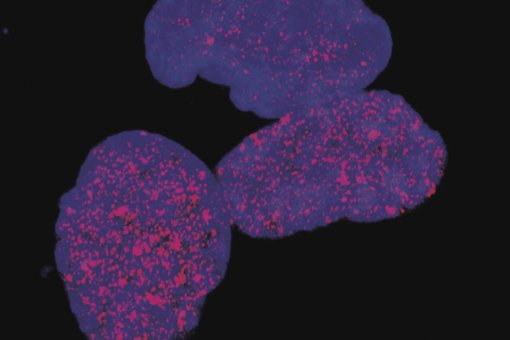

In another paper published in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism, part of the Nature Group, the researchers provided the first evidence that neurons constantly store glycogen but in a different way: accumulating small amounts and using it as quickly as it becomes available. In this regard, the scientists set up new, more sensitive, analytical techniques to confirm that the machinery responsible for glycogen synthesis and degradation existed. In summary, they showed that, in small amounts, glycogen is beneficial for neurons.

“For example, while the liver accumulates glycogen in large amounts and releases it slowly to maintain blood sugar levels, above all when we sleep, neurons synthesize and degrade small amounts of this polysaccharide continuously. They do not use it as an energy store but as a rapid and small, but constant, source of energy,” explains Guinovart, also senior professor at the University of Barcelona (UB).

To observe the action of glycogen, the scientists forced cultured mouse neurons to survive under oxygen depletion. They demonstrated that the first cells to die were those in which the capacity to synthesise glycogen had been removed. The same experiments were performed in collaboration with Marco Milán’s “Development and growth control” group in the in vivo model of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. These tests led to the same conclusions.

The researchers postulated that glycogen is a lifeguard under oxygen depletion, a condition that leads the brains to shut down and that often occurs at birth and in cerebral infarctions in adults, which leads to severe consequences, such a cerebral paralysis.

“It is the first function of glycogen that we have discovered in neurons, but we still have to identify its function in normal conditions and establish how the mechanism works,” says Jordi Duran. Postdoctoral researcher Isabel Saez is the first author of the article out today, which involved the collaboration of ICREA Research Professor Marco Milán’s lab.

The beneficial and toxic roles of brain glycogen are currently the focus of main research lines conducted by Joan Guinovart’s lab.

Reference articles:

Glycogen accumulation underlies neurodegeneration and autophagy impairment in Lafora disease

Jordi Duran, Agnès Gruart, Mar García-Rocha, José M. Delgado-García and Joan J. Guinovart

Human Molecular Genetics (2014 )1–10. AOP 4 february, doi:10.1093/hmg/ddu024

Neurons have an active glycogen metabolism that contributes to tolerance to hypoxia

Isabel Saez, Jordi Duran, Christopher Sinadinos, Antoni Beltran, Oscar Yanes, MaríaFlorencia Tevy,Carlos Martínez-Pons, Marco Milán and Joan J Guinovart

Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism (2014), advance online publication, February 26, 2014; doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2014.33

About IRB Barcelona

The Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB Barcelona) pursues a society free of disease. To this end, it conducts multidisciplinary research of excellence to cure cancer and other diseases linked to ageing. It establishes technology transfer agreements with the pharmaceutical industry and major hospitals to bring research results closer to society, and organises a range of science outreach activities to engage the public in an open dialogue. IRB Barcelona is an international centre that hosts 400 researchers and more than 30 nationalities. Recognised as a Severo Ochoa Centre of Excellence since 2011, IRB Barcelona is a CERCA centre and member of the Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology (BIST).