Images

Participants

Contact

Born in Washington DC in 1983, Dr. Francisco Barriga completed his schooling in Chile and graduated in Biochemistry from the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile in 2008. He joined the first IRB Barcelona/ La Caixa International PhD programme in September of the same year and was awarded his doctorate in 2013. He spent a further 2 years as a postdoc at the Institute and then 6 years at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

In January 2023, he returned to Barcelona to take up the position of Group Leader of the Cancer Genome Engineering Group at the Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO). He holds a prestigious ERC Starting Grant, as well as funding from the Agencia Estatal de Investigación (Proyecto de Generación de Conocimiento, Ayuda Ramón y Cajal, and Consolidación Investigadora).

"In my opinion, IRB Barcelona is in a really strong position right now to become one of the best biomedical research centres in Europe."

How does it feel to be back in Barcelona?

I am excited to be back! Barcelona is home to me, both at a personal and scientific level. It has been a real pleasure to reconnect with my former colleagues and start my group in the context of the vibrant Barcelona biomedical community.

Tell us about how your lab came about.

I was finishing my postdoc in the Lowe Lab at the Memorial Sloan Kettering and was actively looking for positions in the US and Barcelona. I applied for an ERC Starting Grant (which has a 7-year limit from the date of the thesis defense) and in the middle of my search for positions, the European Research Council (ERC) notified me that my grant had been funded. I was so lucky that I got it, and it's a great start to my lab!

The scientific and clinical community at VHIO is outstanding, and I'm excited to learn and contribute at their side to help improve patient care.

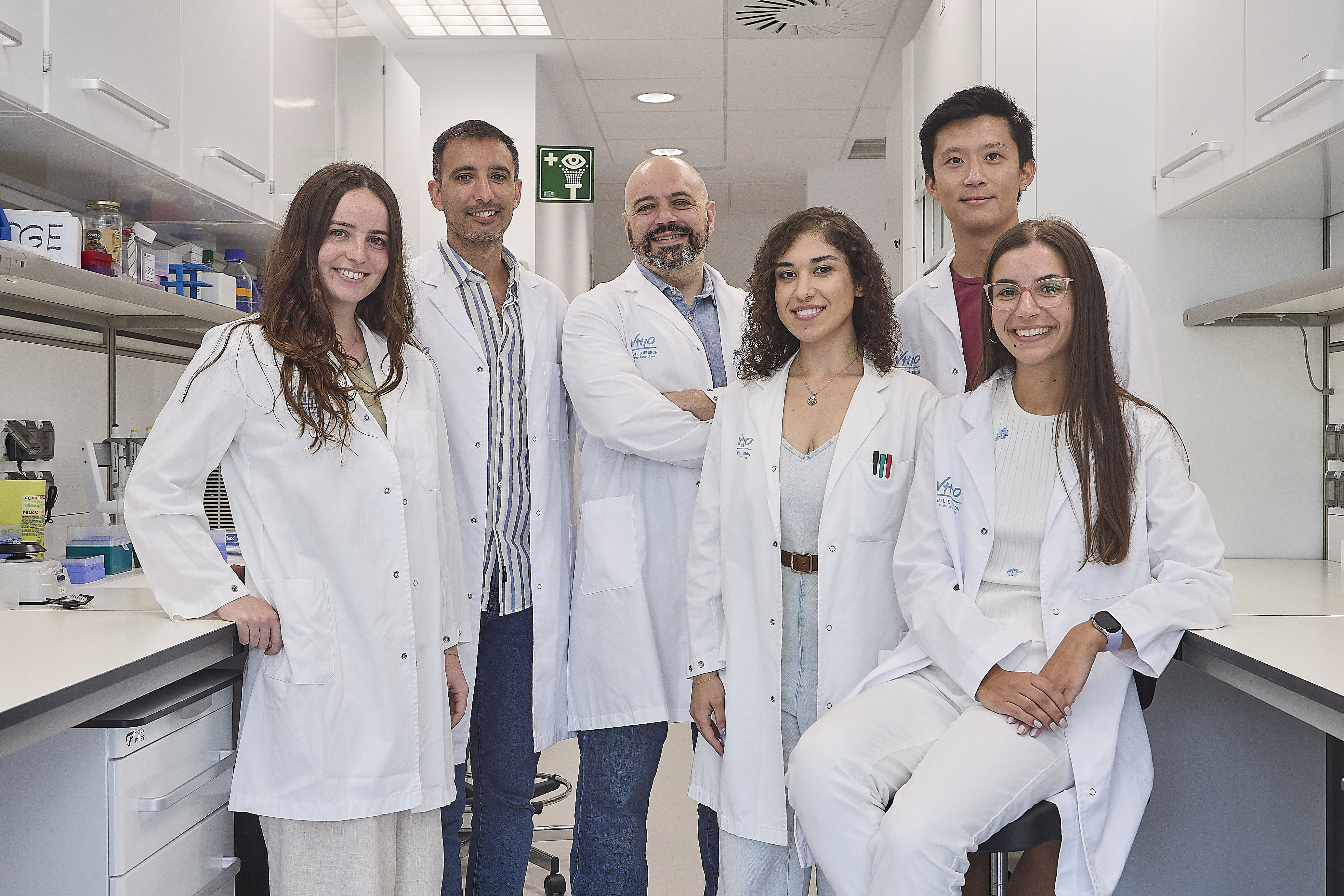

In terms of my group, the lab currently comprises a lab manager, a postdoc, a technician, and 2 students, (and we are a diverse group covering 5 countries). And although it's early days, I’m really happy with how the group has started!

What do you focus on?

We focus on modelling large-scale copy number alterations. A tumour losing or gaining a large number of genes is very recurrent, and these changes are observed with cancer-specific patterns, thus supporting the idea that they are selected for their effects on tumours. However, our understanding of the effects of these genetic changes on the cancer cell is lacking and this impairs our ability to target these cells.

We have realised that the more tumours we analyse, the more patterns are revealed. And while not all tumours are equal, not all tumours are unique either: there are many genetic events that affect a large fraction of tumours. For instance, some that we are studying affect 20% of all types of cancer.

Despite this, how these alterations work remains unknown, so, during my postdoc at Scott Lowe's lab, we developed a method called "MACHETE" ("Molecular Alteration of Chromosomes with Engineered Tandem Elements") to identify, for example, what would happen to the tumour cell if it lost a large region of DNA.

Our lab studies pancreatic cancer, but the methods we use can be applied to all types of tumours.

Where did your interest in cancer start?

This started at a very young age and was largely inspired by my father, who is a pediatric oncologist. Growing up around his work led me to pursue a path where I could contribute to our understanding and treatment of cancer, and where I decided that fundamental research is where I wanted to invest my efforts. After my biochemistry degree in Chile, I knew I had to go elsewhere to continue my career in cancer research.

With this goal in mind, I did my PhD in Dr. Eduard Batlle's group at IRB Barcelona, which is where I learned the trade of being a biomedical researcher.

At IRB Barcelona, I learned a lot about stem cells and cell state heterogeneity. By that, I am referring to the fact that genetically identical cells can behave very differently. We know this is a big part of why tumours don’t respond to therapy. However, the other big part of why they don’t respond is because they are genetically distinct, which led me to change fields for my postdoc.

From your experience in the US, would you say that Americans do science differently?

Absolutely. It is incredibly fast-paced and the sheer volume and quality of labs is impressive! On a personal level, in Barcelona, I learned the foundations of how to be a biomedical researcher, and in the US I not only expanded my knowledge base, but as a postdoc I also learned the skills needed to launch (and hopefully succeed!) an independent group.

"I was delighted when I was accepted to do my PhD in Eduard's lab. I remember that my first day in the lab was 1 September 2008, and I felt that I was starting something important in my life. Fortunately, that turned out to be the case!"

Francisco, let’s go back to your PhD experience. How did you end up at IRB Barcelona?

My journey to IRB Barcelona was interesting. As I mentioned, I had always known I would leave Chile to study cancer. The big opportunity came in 2006 when I met Dr. Joan Guinovart (the first director of IRB Barcelona) at a meeting of the Chilean Society of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Joan mentioned that they had just started a new research institute centred on biomedical research in Barcelona.

While visiting Barcelona over that summer, I contacted Joan and he invited me to visit the Institute, where I met Dr. Eduard Batlle and Dr. Roger Gomis. IRB Barcelona was in its infancy, and Eduard and Roger were the only PIs in the Cancer Programme back then. How things have changed!

I then applied for an IRB Barcelona / “la Caixa” International PhD fellowship in 2007. In March 2008, I went for an interview at IRB Barcelona and was delighted when I was accepted to do my PhD in Eduard's lab. I remember that my first day in the lab was 1 September 2008 and I felt that I was starting something important in my life. Fortunately, that turned out to be the case!

What advice would you give to PhD students?

This is the time in your career when you hone your skills, identify problems, create experimental approaches to solve them and learn to be a scientist. You should definitely enjoy it, but it is not a walk in the park. Pushing the boundaries of knowledge is a challenge. Enjoy it but keep in mind that everything that you are doing is helping you create an extremely powerful framework of the way you think and solve problems, a broadly applicable skill.

With respect to the members of your lab, what kind of PI are you?

My experience has defined the kind of PI that I am. In my first lab meeting, I gave the team a handbook I wrote about the lab culture that I want us to have. It sets out my responsibilities as a mentor (support, supervision, grants, fostering a good lab environment, etc), as well as their responsibilities as lab members (curiosity, commitment to their projects, teamwork, etc).

In my experience, my best work has always come about when I am having a good time. In this regard, I want to build a safe place where people can fulfil and enjoy their careers.

Since leading my own group has always been my goal, I have had a lot of time to reflect on what it means to me to become a PI. I get the freedom to ask scientific questions that intrigue me, and I also get to train the next generation of scientists. These are responsibilities that I take very seriously.

What is your take on options beyond the bench vs. positions in academia?

At the end of my PhD, I did receive an offer in industry, but since I really liked academic research, I wanted to try and see if I could get a position that fit with what I wanted to achieve. It's also true that once you leave academia, it’s very hard to get back. As I mentioned, this is a very personal choice and I have many colleagues with fulfilling careers in industry and other non-academic endeavours.

If anything, those of us who stay in academia are outliers, and we need to raise students' awareness of all the other opportunities available for people with PhDs.

My advice is that if you truly believe that an academic position is for you, then go for it! And despite all the issues, it’s a fantastic job and community. You get to be surrounded by brilliant people from all over the world, you have incredibly stimulating conversations about big subjects, and you have freedom rarely found elsewhere.

What is your current relationship with IRB Barcelona and how do you envisage its future?

I visit at least once a month since I have ongoing collaborations and many good friends work there. I like to catch up with them and discuss how we could solve different questions together.

In my opinion, IRB Barcelona is in a really strong position right now to become one of the best biomedical research centres in Europe. I think that we should start building bigger networks comprising all research institutions in Barcelona because we complement each other very well.

About IRB Barcelona

The Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB Barcelona) pursues a society free of disease. To this end, it conducts multidisciplinary research of excellence to cure cancer and other diseases linked to ageing. It establishes technology transfer agreements with the pharmaceutical industry and major hospitals to bring research results closer to society, and organises a range of science outreach activities to engage the public in an open dialogue. IRB Barcelona is an international centre that hosts 400 researchers and more than 30 nationalities. Recognised as a Severo Ochoa Centre of Excellence since 2011, IRB Barcelona is a CERCA centre and member of the Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology (BIST).